A Woman's Controversial Obituary for Her Mom Sparked Outrage — But I Believe We Need More of This

The Importance of Honesty in Obituaries

Many of us have been told, “don’t speak ill of the dead.” But what happens when someone who caused trauma dies? The idea that the deceased should be exempt from criticism simply because they’ve passed on is outdated and in desperate need of revision. For survivors of abuse, their abuser’s death might be their first opportunity to safely share their stories.

Cultural myths about the everlasting love of families — especially mothers — are beginning to be contested, as seen in Jennette McCurdy’s memoir, “I’m Glad My Mom Died.” However, these honest recollections are often denied or disbelieved. A viral obituary detailing Gayle Harvey Heckman's lifetime of abuse at her mother's hands was pulled by a publication, which described it as a “spiteful hate piece against a beloved member of our community.” This response shows how uncomfortable society is with acknowledging the possibility that someone made heinous choices while alive.

The news media and most people in general seem to have specific expectations for how one is supposed to publicly perform grief. When someone dies, we’re expected to attend their funeral, cry, miss them, and write a flowery obituary. The unspoken rule is that we are never to suggest that the dead may have behaved reprehensibly in life. Any mention of a traumatic legacy is dismissed, as was the case for Heckman.

Personal Experiences with Obituaries

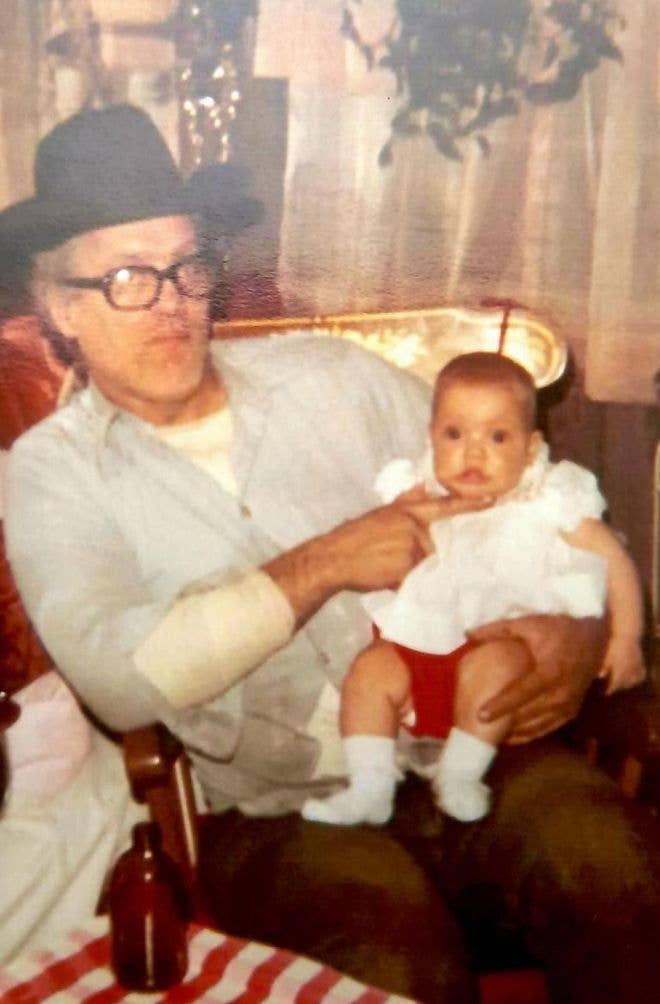

I myself am no stranger to trying — and failing — to publish an honest obituary. When my grandfather, whom I called “Pop,” died, I attempted to publish an honest paragraph about his life. I saw firsthand how he overcame a brutal marriage and lived his final years in Florida away from his ex-wife.

In the 1980s, my father picked up Pop from the side of a country road where he’d been walking barefoot, crying, after being kicked out of their home without a cent. As a child, I watched Pop sleep on our couch in Brooklyn with nowhere else to go, planning his next move. When I became an adult, we spent hours on the phone as he rehashed his regrets — including his marriage to my grandmother.

I am married, so I understand that every relationship has two sides. However, as a direct recipient of abuse by this same woman, my grandfather’s experiences deeply resonated with my own. My grandmother’s emotional, physical, and financial abuse touched every generation in our family.

The Impact of Abuse and Trauma

In 1980, she kicked my teenage parents and me out of her house when I was an infant. She decided on a whim that my underemployed father and postpartum mother could make it on their own, without a single resource. Family lore tells that the motivation had something to do with an argument over an untidy bathroom.

Later, after the unthinkable position she put us in, my grandmother publicly took credit for what my parents were able to overcome. Her lack of self-awareness will never not be breathtaking to me. When I was a young child, after my parents reconnected with my grandmother, my father felt it necessary to supervise her visits with my little sister and me, citing how physically and emotionally hostile she’d been with us when she thought no one was watching or listening.

Years later, I turned to trauma-informed therapy to come to terms with my upbringing and began to understand just how far-reaching and insidious my grandmother’s influence was. This woman’s most morally corrupt behavior was often carried out in private, reserved only for those who lived under her toxic thumb. Therefore, casual friends, acquaintances, or anyone on the periphery of her life would find such details hard — if not impossible — to believe.

This is why society’s stance toward obituaries needs rethinking. Those who were not previously aware of a person’s traumatic experiences can gain insight into what actually took place, and survivors of abuse can lift the veil of silence and move towards healing.

The Healing Power of Honest Obituaries

The best revenge is a life well lived. Upon reflecting on my grandfather’s life, I considered how leaving his abusive marriage and finding happiness as an Elvis devotee in the Sunshine State was perhaps his biggest accomplishment. He was also a veteran who found his post-service calling in restoring cars.

In writing about his life, I wanted to capture his triumphs and trials, but was shot down again and again. The newspapers wanted to hear nothing about the abuses he’d suffered and all that he had overcome on his path toward peace. My only option was to write something palatable and half-true — an easy-to-swallow fairy tale readers could easily and safely digest.

As much as I resented being silenced, the life Pop lived gave me plenty to work with. He was a truly beloved member of his community who unconditionally loved his family. My grandmother died last fall. As far as I know, she remained abusive to her last breath. I don’t believe there is any way to honor her life as she chose to live it, and for this reason, no one in the family has written an obituary for her. Perhaps this essay is the closest I’ll ever get to telling what I know to be the truth about her and the pain she inflicted.

The Truth Matters

Writing honest obituaries, for some, can be healing. Invalidating and dismissing a survivor’s experiences for the sake of our own emotional comfort can be retraumatizing. And telling a person that their experiences no longer matter because their abuser passed on is ghoulish. That’s not how the lasting effects of abuse and trauma work. A newspaper editor is not in any moral position to decide whether an obituary is a “spiteful hate piece.”

While it’s true that the deceased cannot defend themselves against any claims made about how they lived their lives, they also can no longer be held accountable for doing harm. Death hands them a full exoneration. Because of this, an honest obituary may be a survivor’s only path toward closure. As American novelist Anne Lamott said, “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” These are wise words for the rest of us.

I do not know the intricacies and intimacies of Heckman’s life — or her mother’s — beyond what was originally published by her, but I believe her. And I believe that telling our stories, however bleak or agonizing they may be, can be crucial to moving forward, processing trauma, and finally healing. Writing honest obituaries — whether it’s for a family member or a world leader — isn’t about getting even or besmirching someone’s good name and it certainly isn’t fun. It’s about telling the truth, holding people accountable for what they did, and hopefully, in doing so, finding a way to become whole again.

Need help? In the U.S., call 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) for the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Christina Wyman is a writer and teacher living in Michigan. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, New York Magazine, ELLE Magazine, Marie Claire, The Guardian, and other outlets. She hopes that her essays about intergenerational trauma contribute to destigmatizing the survivor stories that emerge from abusive and toxic family dynamics.