Blazing Games: The Heat Hazard in Football Stadiums

The Heat Inside College Football Stadiums

When Vanderbilt University football fan Douglas Dill set out with his son the morning of October 4 to watch their team play rival University of Alabama, he didn’t expect his game-day experience to include a gurney ride to a medical facility inside Bryant-Denny Stadium. But by the fourth quarter in Tuscaloosa, with the sun beating down on the upper decks, the 60-year-old needed medical help.

“It was smoking hot up there,” said Dill, who traveled from Nashville for the game. “The sun was burning me through my clothes. I needed to get up and get some fluids in me or I was going to go down big time. I was starting to get light-headed.” Dill, who operates a courier service with his wife, said he drank water throughout the day but that he had none left by the middle of the fourth quarter. His son and a stadium paramedic helped him down the steep upper-deck stairs to where additional emergency medical personnel were waiting with the gurney.

Paramedics treated Dill for dehydration as well as low blood sugar and monitored his blood pressure, which had climbed above normal. Dill has type 2 diabetes but does not usually have high blood pressure. While Dill missed the end of the game, he recovered enough for his son to drive him home.

Dill is one of hundreds of fans who have fallen ill from extreme heat in recent years at college games in powerhouse stadiums in the Southeastern Conference. The SEC, a collegiate athletic association, represents programs across a dozen states and accounts for 9 of the country’s 13 largest football stadiums.

ICN reviewed temperature studies of heat conditions at Auburn University, the University of Alabama, and Mississippi State University, and collected its own temperature measurements during two games in October, one at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa and the other at University of Alabama at Birmingham.

An Inside Climate News analysis of data from inside these Southern stadiums found that temperatures can spike for hours, from 10 degrees to 16 degrees Fahrenheit higher than outside heat, depending on the venue. Concrete surface temperatures in seating areas of the Tuscaloosa stadium measured over 130 degrees F.

Those high temperatures had consequences. Auburn University averaged well over 100 emergency calls per game in 2024, with the majority being heat-related. Halfway through the 2025 season, Alabama was averaging 60 to 65 medical calls per game, with 50 to 75 percent of calls during day games related to heat, according to interviews with medical personnel, though university officials provided lower numbers.

Auburn administrators said they are aware of excessive heat risks for spectators and are trying to enhance cooling efforts. University of Alabama officials said in a statement that “fan safety is a top priority” and that it aims to safeguard fans by providing cooling stations and emergency responders during games in Tuscaloosa.

The university informs spectators about the free water stations and first aid through websites, apps, social-media channels, and in-stadium announcements from the public-address system and on video screens, the statement said. The University of Alabama at Birmingham, which has a stadium about half the size of Tuscaloosa’s arena, has also provided cooling stations.

Still, none of the universities have made changes that could make the biggest difference in lowering the potential for illness: shifting game times or the season itself. That would require a much greater degree of cooperation — particularly because of the financial consideration of big college football — across athletic conferences.

Medical professionals said that spectators need help in assessing heat risks and making safe choices on game days.

“People tend to really want to be there, and so they will endure perhaps more physical discomfort to stay there throughout the event than they would if they were just taking a walk or doing stuff on their own,” said Dr. Cheyenne Falat, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of Maryland who specializes in weather-related and heat illnesses.

Another factor that likely affects fans’ ability to withstand heat is alcohol consumption. Auburn, University of Alabama, and University of Alabama at Birmingham have recently allowed the sale of alcohol at games. Medical logs reveal that alcohol was a complicating factor at Auburn University for people treated for heat-related illnesses during games. Auburn began selling alcohol in 2024, the other schools in 2022.

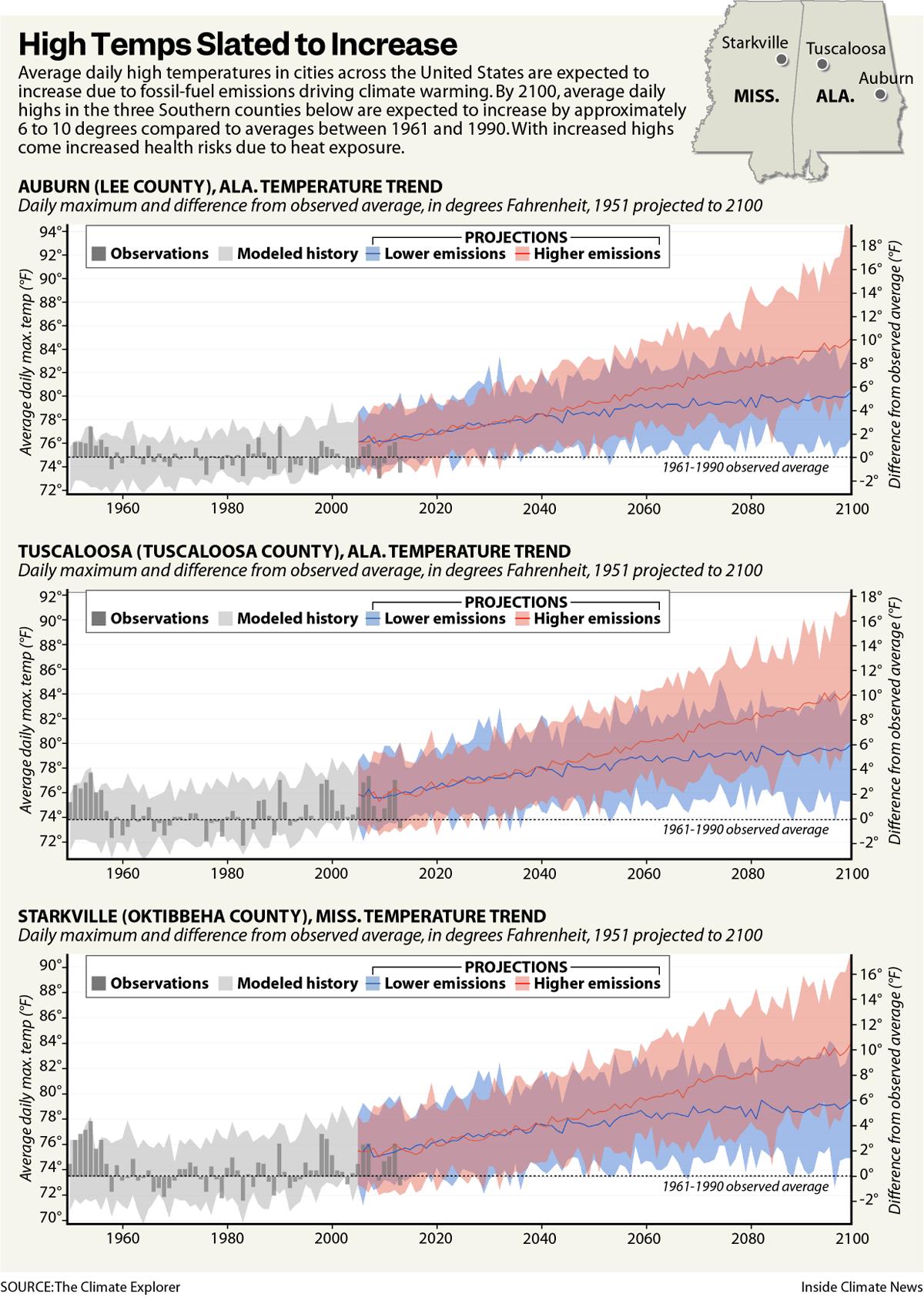

As climate change intensifies, heat risks are likely to increase.

A federal government analysis of climate modeling predicts that by the 2040s, the average maximum daily temperature in Tuscaloosa, the home of the University of Alabama, will be 5 degrees F above the average registered from 1961 to 1990.

A researcher who has tracked heat risks at Auburn University’s Jordan-Hare Stadium — at 88,043 seats, second in capacity in the state only to the University of Alabama’s 101,821 — said his ongoing work is aimed at crafting possibilities to alleviate potential harm.

“I don’t want to say it’s out of the realm of possibility, per se, but I would say in terms of solutions, I think we have to face the reality that we are, in fact, going to have [midday] games,” said Brandon Ryan, an Auburn graduate researcher and teaching assistant in the department of geosciences. He’s been measuring in-stadium temperatures since 2023. “If that’s unavoidable, how do we tackle that problem?”

First responders busy

For a few months every year in Alabama, Saturdays are sacred. College football reigns as the king of sports across much of the South, and in this sun-drenched state, two fields hold dominion: the Alabama and Auburn gridirons.

But gathering to yell “roll tide” or “war eagle” as teams compete in these massive concrete stadiums comes with costs. First responders at these universities increasingly spend days, and sometimes nights, rescuing football fans exposed to excessive heat.

Wes Michaels, emergency services coordinator at the University of Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium and a lieutenant with Tuscaloosa Fire Rescue, said 60 medical professionals were on hand for the Crimson Tide’s October 4 game against Vanderbilt, with its capacity crowd.

“You think, man, 60 people, that’s a lot,” Michaels said. “I’ll tell you, with 100,000 people in here, it gets really, really busy. Everybody is doing something, tending to a patient.”

Researchers at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa raised an alarm 15 years ago about in-stadium heat. An Auburn University research team, led by Ryan, continues to study heat stress among fans on much-anticipated game days at Jordan-Hare.

Ryan knows about sacred Saturdays — especially the hot ones.

One of them came on September 21, 2024, when Auburn played Arkansas.

Kickoff that day at Jordan-Hare was at 2:30 p.m. The high temperature at the university airport station was 88 degrees. The heat index, a measure of the “feels like” temperature that accounts for humidity, was around 90 degrees from noon through 5 p.m.

Inside Jordan-Hare, the 13th largest stadium in the United States, the temperature was much higher.

“It was brutal,” Ryan said.

He saw some fans in higher tiers leave their seats in search of shade in the stadium walkways. Many guzzled water. Others were less able to cope. Heat indices in the stadium, according to temperature sensors Ryan installed in seating sections across the facility, ranged from 97 to 114 degrees.

“They were literally dragging people out of the way,” Ryan said of medical personnel. He said his review of emergency service records found that first responders received 214 medical calls during that game, the majority of which were heat-related.

Ryan was not wholly surprised by the illnesses. He had been studying stadium heat for more than a year then, working with a faculty advisor and members of the university’s public safety team. Because of his ongoing research, Ryan has become the institution’s go-to expert on stadium heat, offering a scientific approach with a bit of a fan’s heart.

“I don’t want it to have to come to somebody dying, and maybe now we’re doing something about it,” Ryan said of his interest in stadium heat. “I don’t want it to be someone I know. I don’t want it to be one of my students.”

Ryan’s research conclusions and related recommendations have been shared with university officials and offer some sobering conclusions about game-day health risks.

Temperature and humidity observations measured throughout Jordan-Hare Stadium from 2023 to 2025 revealed that the heat index in the facility regularly reached 10 or more degrees above that measured outside its walls. During some games, heat indices inside the stadium, built in 1939, rose to over 100 degrees, according to Ryan’s research.

Ryan said that large sports stadiums like Jordan-Hare can trap excessive heat for several reasons. High-capacity stadiums pack in spectators, and people who sit for the average three-hour game may find themselves hostage to the sun. High humidity is also a problem, limiting the body’s natural cooling ability.

James Spann, chief meteorologist for the ABC affiliate in Birmingham, attends all the University of Alabama home games in Bryant-Denny Stadium as a weather advisor to coaches. Known for engaging live broadcasts during severe weather events and for focusing on weather-safety education, Spann helps spectators stay on top of the weather, too. He issues updates that are shared on the stadium’s large video screens.

Body heat adds to the thermal load inside the stadium, increasing air temperature by 2 to 5 degrees, Spann said. Artificial turf can heat up to 20 to 30 degrees hotter than the ambient air, he continued, and concrete and metal stands absorb and radiate heat.

And where a fan sits — in the sun or in the shade — can make a big difference, too, according to Spann. Seating areas in the sun in Bryant-Denny Stadium can be 10 to 15 degrees warmer than shaded areas, “so if you’ve got a day where it’s 90 degrees, it could be 105 in the sun,” he said.

Spann said fans know this, but 7 of 8 spectators randomly interviewed during the October 4 game underestimated how hot it got inside the stadium, giving the day’s forecasted high in the mid-80s or a lower number. An Inside Climate News reporter measured temperatures as high as 96 degrees in the stadium that day.

Asked about whether the public and designers and operators of sports stadiums need to take rising maximum daily temperatures into consideration in their decision-making, Spann referred such questions to Alabama’s state climatologist, John Christy, who notably rejects mainstream climate science. Christy has argued there is no causal link between CO2 emissions and a warming climate.

Even when weather conditions are overcast and breezy, as they were during University of Alabama at Birmingham’s October 4 game against Army in Protective Stadium, a significant temperature difference can occur between inside and outside the stadium, which seats about 45,000 people.

That day, kickoff was at 11 a.m. and measurements taken by an Inside Climate News reporter that day recorded a difference in air temperatures of as much as 10 degrees — depending on sun exposure — even in a newer stadium. Protective Stadium opened in 2021.

Ryan said his data at Auburn’s Jordan-Hare Stadium shows that sun exposure has a clear and measurable impact on the relative comfort of a particular seat.

“Day games are extremely problematic,” Ryan said. “Night games, not as much.” Over three seasons of observations, Ryan said his measurements recorded heat index values exceeding 115 degrees at least once during both the 2023 and 2024 seasons, both on late September day games.

During that same two-year period, elevated temperatures inside the facility have led to more than a thousand heat-related medical calls to first responders, records show.

On the day of the 2024 Auburn-Arkansas game, Ryan said, sensors in 7 of 9 seating sections across Jordan-Hare measured “feels like” conditions above 103 degrees. Temperatures exceeding that are characterized as dangerous by experts, making “heat cramps or heat exhaustion likely, and heat stroke possible with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity,” according to the National Weather Service.

Ryan has also relied on data from Auburn university officials to collate his findings. In 2023, there were as many as 43 heat-related medical calls per game, university records showed.

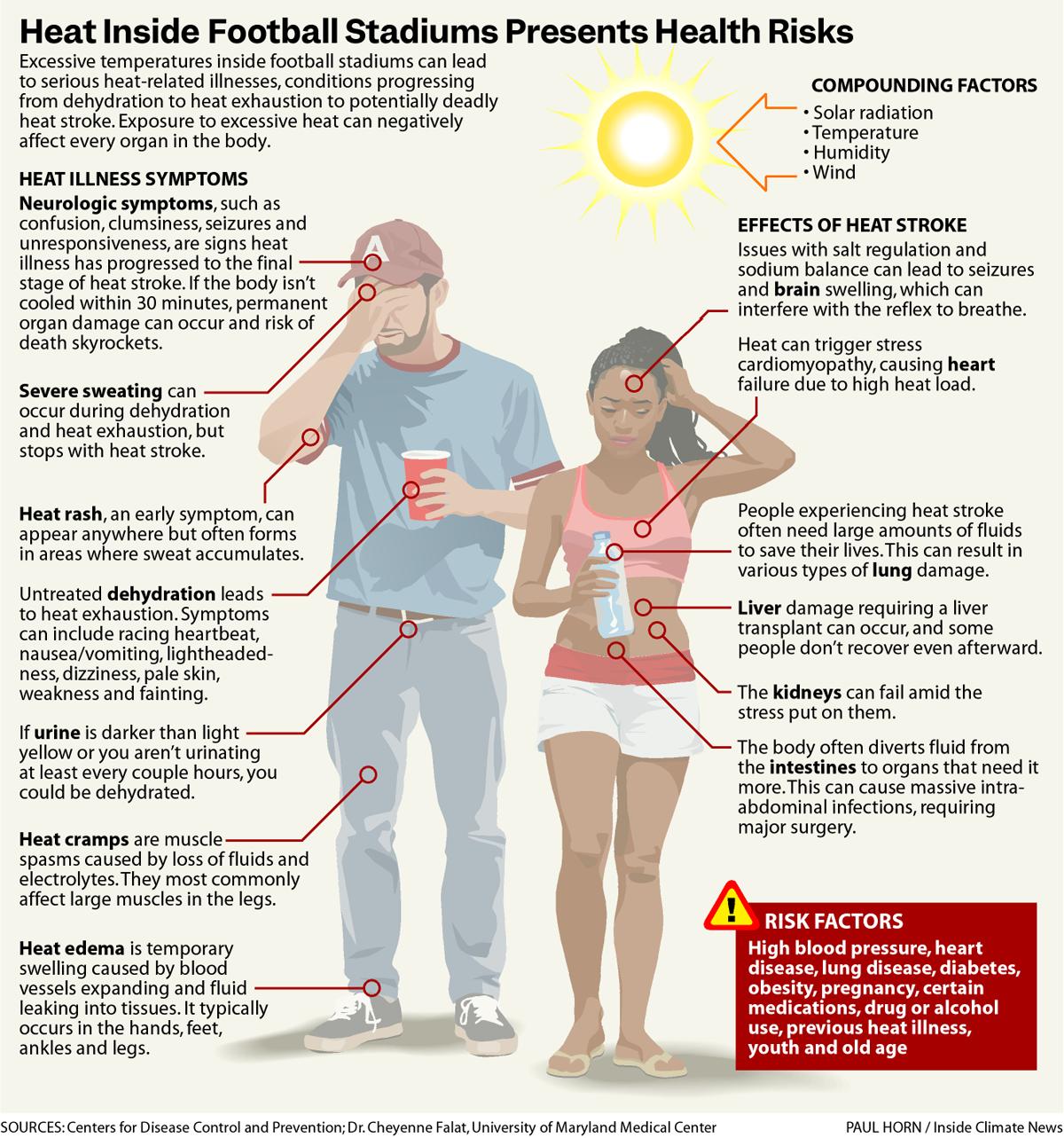

Spectators at Jordan-Hare suffered heat-related illnesses including nosebleeds, seizures, dehydration, and low blood sugar and complaints of feeling lightheaded and dizzy. Other fans called first responders for abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, heart palpitations, and difficulty breathing.

By 2024, medical calls increased significantly inside the stadium, according to Ryan’s research.

First responders averaged 161 calls per game for a total of more than 805 calls at all home games, the majority of which were for heat or cardiac-related events, records revealed.

In the 2023 dataset, of the 113 emergency calls attributed to heat-related illness, 44 involved individuals who fainted or were reportedly “about to faint.”

Numerous heat-related incidents reported inside Jordan-Hare included alcohol as a contributing factor, according to medical logs reviewed by ICN. Although the school did not begin to sell alcohol inside the stadium until the 2024 season, experts say alcohol use may have exacerbated the risk of heat-related illness.

Alcohol contributes to heat illness in two ways, said Falat, the University of Maryland expert on weather-related illnesses and the university hospital’s assistant medical director for the adult emergency department.

Alcohol dehydrates, she said, and dehydration is an initial stage of heat illness that can lead to heat exhaustion and heat stroke. Then, “as you drink more and more, your ability to recognize your symptoms becomes impaired … and that’s when we start to really, really enter that danger zone,” she said.

Spann, the meteorologist, said alcohol consumption during early-season day games at Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa has proved to be a significant problem. “The worst thing you can do is drink a lot of alcohol on a hot day out there in the sun, and nothing good is going to come out of that,” he said.

The university challenge

Since 2023, Ryan has been submitting recommendations to Auburn University officials, outlining the empirical data from the research team and making policy suggestions aimed at mitigating health risks.

Ashley Gann, Auburn’s public information officer for campus safety and security and a meteorologist herself, said Ryan’s work “was incredibly valuable” and has helped administrators build a strategic heat plan.

“His work helped validate the importance of our existing heat plan and gave us the data we needed to refine it even further,” Gann said. “Thanks to Brandon’s study, we were able to concentrate resources in the areas of greatest need and engage in more strategic pre-planning for both football and baseball events. His contributions have strengthened our ability to protect fans and staff from heat-related risks.”

Earlier research at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa stands as a precursor to Ryan’s findings, which he is continuing to refine and plans to publish.

Fifteen years ago, researchers conducted a study similar to Ryan’s at Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium.

Barrett Gutter, now an assistant professor of meteorology at Virginia Tech, tracked temperature data in Bryant-Denny Stadium as part of his student research in 2009. The facility was constructed in 1929 and has been expanded multiple times.

Gutter collected readings at six locations inside the stadium during a game in October 2009 and compared them to temperatures recorded at the National Weather Service station at Tuscaloosa Regional Airport. He found “significantly warmer temperatures” at each location inside the stadium.

Temperatures in the concourse areas were up to 17 degrees higher than those at the airport, while temperatures at field level seating and in the upper decks were recorded 10.5 degrees and 13 degrees warmer, respectively.

Gutter’s study was conducted before a stadium expansion in 2010 that enclosed the south end zone and added an upper deck with about 9,000 seats. The stadium also added artificial turf sidelines in 2023. Gutter said in a recent interview that temperature differentials likely would be greater today.

“When you close in a stadium like they did, it really limits the amount of air flow and circulation you’re going to get in there,” he said. “You basically are just in a bowl, and so all of that heat has a harder time basically evacuating that stadium. When you have an open end zone, you have a way for that heat to escape.”

Gutter’s research provided some telling geographical detail about seating risks then. Field-level temperatures between 3:15 p.m. and 5 p.m. were about 6 degrees higher on the east side versus the west side of Bryant-Denny Stadium. The western section of the upper deck casts a shadow that gradually covers seating on the western side of the stadium during that time period, Gutter observed. The shadow cooled the temperature sensor in that location.

Workers are facing dangerous heat — even inside fast-food restaurants

Frida Garza

Gutter later pursued research on stadium heat at Mississippi State University, where he was a professor. Last year, he and three other researchers published a study in the journal Atmosphere that analyzed the impact of heat exposure on spectator health at Mississippi State’s Davis Wade Stadium.

The researchers deployed 50 sensors around the arena and measured temperature and humidity from August through November 2016. They compared that data with readings at a weather station near Mississippi State as well as first-aid and emergency medical data from the university’s office of emergency management.

“What I got out of that study, more so than anything, was, on a spatial and temporal scale, how much fluctuation you see even through a game, which is the influence of shade,” Gutter said.

Gutter said the Mississippi study solidified findings from the Bryant-Denny research. Heat-related illness comprised up to two-thirds of cases requiring first-aid at Mississippi State. The majority of heat-related incidents occurred in the most thermally oppressive parts of the stadium, according to the study.

The study concluded there was a need for greater monitoring of heat exposure inside stadiums, better education for spectators regarding heat-mitigation strategies, and stadium design modifications to improve circulation, increase shade and reduce crowding.

The search for water

On the day in October that Douglas Dill fell ill at the University of Alabama, a reporter for Inside Climate News recorded temperatures inside and outside Bryant-Denny Stadium. The readings were recorded from 12:08 p.m. to 4:55 p.m. and approximately every 30 minutes during the game. Air temperatures were measured using a probe thermometer, and an infrared thermometer was held above concrete and metal in seating areas to measure surface temperatures.

Temperatures were recorded on the eastern side of the stadium, where spectators were in direct sunlight for the entire game.

At 2:30 kickoff time, an air temperature reading in the upper deck of the stadium was 11 degrees warmer than the temperature recorded at the airport. Temperatures measured inside the stadium ranged from 85 degrees to 96 degrees.

Emergency calls

Emergency medical staff who operate a 10-bed first-aid facility at Bryant-Denny Stadium said on October 4 they had received an average of 60 to 65 medical calls per game at that point in the 2025 season. Not all calls are heat-related. The percentage of heat calls depends on game time, temperature and time of year, according to Michaels.

“Heat is one of our biggest challenges we face,” Michaels said.

During the October 4 game, 50 percent to 60 percent of calls were heat-related, with most people suffering from heat exhaustion or fainting, said Michaels, who has worked as a first responder at the stadium since 2009. Problems slowed in the second half as shade spread over the western half of Bryant-Denny Stadium, he said.

On September 13, during the Wisconsin-Alabama game that kicked off at 11 a.m., every bed and chair in the first-aid facility was occupied, Michaels said. The high temperature outside the stadium that day was 92 degrees.

There were more than 70 EMS calls during that game, and approximately 75 percent were heat-related, Michaels said. “The Wisconsin game was very challenging as far as managing the heat-related stuff,” he said. “Crews did a really good job of getting people to where they needed to go, whether it be a cool zone, whether it be one of the first-aid rooms or whether it be the hospital.”

There have been games with as few as about 10 calls, he continued, and those are typically at night or late in the season.

Michaels said people planning to attend a game should know what the physical demands are and consider their health conditions. They should be aware, for instance, that they might have to walk a mile and half in the heat just to get to the stadium, then walk up spiral ramps and stairs to get to their seats, he said.

“That can be a lot,” he said. “Folks have to know their limitations.”

Other medical professionals said much the same, adding that people should wear ventilated clothing and shaded hats, use cooling rags and stand near fans when possible on hot days. Elderly people, young children and those with certain medical conditions or who are taking particular medications are especially vulnerable to heat risks.

Heat already kills more Americans than any other weather-related hazard, according to the National Weather Service, and climate change is leading to more frequent, intense and longer-lasting heat waves, Falat said.

“It’s absolutely expected that deaths and other complications from heat-related illnesses will rise as those events rise, but it is also an opportunity for us as a society to really increase our public health awareness of these events, because the statistics don’t have to follow suit,” she said.

Dr. William Barton, assistant medical director of the emergency department at DCH Regional Medical Center, located 2 miles from Bryant-Denny Stadium, said the football season also affects his emergency department. Between 50 and 100 people are treated at the stadium’s first-aid facility during some games, he said. Paramedics send an average of 10 to 20 people per game over to the medical center’s emergency room, Barton said, and the majority are experiencing heat-related illness.

The university provided far lower numbers of illness to Inside Climate News.

“So far this season, EMS has responded to 18 heat-related calls during three home football games,” according to the university statement dated October 10. “Last season, EMS responded to 26 heat-related calls during seven home games. During the past two seasons, two fans were transported to the hospital for heat-related illness.”

“Hydration is the big thing,” Barton said. “That’s where most people run into trouble. Your skin does what’s called evaporative cooling, and in the process of that, you lose a lot of fluids from your body. You are going to find yourself in a position where you’re becoming dehydrated, and you really didn’t know that you were.”

Minor changes, major stakes

Universities are making some headway in addressing heat risks in their football stadiums.

The University of Alabama added cooling stations a decade ago, and that has made a difference, Michaels said. “Before those cooling stations were installed, it was nothing to have 100 calls in a ball game,” he said about Bryant-Denny Stadium. “And when the university invested the resources to permit those cooling stations, it drastically affected the call volume.”

Both Gutter and Ryan said that there are other small steps that universities can take such as improving air circulation, creating more shaded areas in the stadiums, increasing access to cooling stations and improving education about heat-related illness.

Decisions that could limit the most risk, experts said — banning midday games during warmer months, enclosing stadiums or building climate-controlled facilities, and even shifting the football season to later in the year — do not seem likely.

Global sports have begun to adapt to the realities of a warming climate, Ryan said, and some leagues may be setting an example for U.S. athletics.

“FIFA had to change the way they did the World Cup,” Ryan said. “We even saw it with the Paris Olympics. If the Olympics are having to think about this sort of stuff, we’re probably gonna have to think about these things too.”

Heat-related deaths, Ryan said, are ultimately avoidable.

“I care about this university a lot. I care about my students a lot. I want them to come to the game to watch the game, and I don’t want them to worry about their grandma passing out,” he said.

Douglas Dill doesn’t regret his day at Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium. His team lost, 30-14. But he said Vanderbilt played a good game and his heat-illness episode won’t deter him from witnessing future ones.

“I love football, and nothing will keep me away from it,” Dill said.